When people comply with an action or tolerate a situation they know is harmful or wrong, fear is often a factor. Fear—of punishment, of the unknown, of one another—often prevents us from protecting and connecting with each other. Powerful actors must keep us convinced that it’s the people around us—everyday folks whose struggles overlap with our own—who pose the greatest threat to our safety, well-being, and happiness. It is the grandest illusion ever created: in a world where corporations and world governments are poised to annihilate most life on Earth, we are made to believe that other disempowered people are the greatest danger we face.

Of course, many of us know this is not true, at least intellectually. We know that the military and corporations are the primary drivers of climate chaos. We know that governments maintain conditions that generate despair and therefore produce interpersonal violence. And we know that under changed conditions, we would have far less to fear in the world, both from the system and from other people. We know that in a society where everyone’s needs are met, we would no longer need to fear getting sick and being unable to pay for our care, or losing our jobs and going hungry, or being hurt by desperate, disillusioned people. Yet many of us accept the violence, limitations, and boundaries imposed by the system as though they are natural laws—inalterable, inevitable, and final—and view everyday people as an existential threat to control, contain, and manage.

Obviously, other people can and do harm us, regardless of how much we share. But the dynamics that alienate us and enable harm are wholly alterable. People are capable of generating social mechanisms and relations that foster safety and understanding within communities. People are capable of overcoming, or at least negotiating, difference for the sake of their common interests, especially in moments of crisis. As the unprecedented flourishing of mutual aid projects during the pandemic has demonstrated, many people respond to communal crisis with generosity and shared concern. The idea that disasters autogenerate panicked, aimlessly violent hordes of people who must be controlled with an iron fist is an authoritarian fever dream. While the powerful would have us believe that frightened people are always selfish and hypervigilant, cooperation and collaborative care are common human responses to disaster.

People across history have largely turned to one another for comfort, sustenance, and protection in moments of crisis. Acknowledging this truth threatens a social order built on the myth that we need authority to protect us from our own chaotic impulses in times of crisis. The state sees communal care as an ideological threat. This is why mutual aid movements are routinely targeted and undermined by the United States government. Mutual aid projects are a manifestation of power that contradicts the state’s primary narrative about what it is, who we are, and whose purpose it ultimately serves.

But capitalism requires an ever-broadening disposable class of people in order to maintain itself, which in turn requires us to believe that there are people whose fates are not linked to our own: people who must be abandoned or eliminated. Absent that terrible belief, we would not tolerate the horrors that unfold around us each day. We would be collectively enraged that people live unsheltered and hungry or die of treatable illnesses because they lack money. We would be horrified that millions of people live in the bondage of the prison system and that people die in the process of struggling to reach unwelcoming borders in the hopes of salvation. Many of us are deeply upset about these things, but this manufactured politics of disposability and the fears that enable it prevent people from taking action against these harms. There are many layers of fear associated with this abandonment: fear of what would happen if the system no longer managed our lives, fear of being devoured by the system ourselves, fear that we cannot win, and perhaps most dauntingly, the fear that we cannot do any better than this, that our hopes to the contrary are the utopian dreams of childish idealists. These fears create a psychic fortress around the death-making forces that are killing us in real time.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

Fortunately, the death-makers of this system have never gone unopposed. There have always been dissenters and freedom fighters organizing against the violence and avarice of capitalism and white supremacy. From prison–industrial complex abolitionists organizing to free people from cages to Indigenous people defending their ancestral lands around the world, these battles have powerful lineages.

Joining the ranks of such struggles may come naturally to some. For many people, though, choosing to believe that change is possible and that it can only come from working in concert with other people requires tremendous courage. Challenging the mythologies of this system, reordering our fears, and investing ourselves in collective struggle are huge steps, and they are not steps most people will take merely because conditions are deteriorating.

Organizing gives us the opportunity to do more than map out the monstrosity that is the system; it allows us to build bonds between people in unique and powerful ways. By expanding our relationships and embracing interdependence, we can leverage power against the threats we face and extend care amid crisis. We can courageously reach out and connect with other people, even if we feel like we don’t have much in common with them. When we experience a taste of collective power, our courage will grow, as we recognize that we are stronger together and that we are not alone.

When we are no longer ruled by a manufactured fear of one another, we experience a form of liberation. It is not a total liberation, as the structures that oppress us are, for now, very much intact, but we experience a kind of unshackling that allows us to begin the process of dismantling individualism—a violent ideology that has siloed us and stifled our collective potential. When we challenge our anxieties about “other people,” and begin to see unlikely points of connection as points of potential stability and strength, we become more powerful.

Unraveling our fear of one another is a multilayered cultural project. After all, it’s undeniable that people sometimes hurt each other, and many people are used to following certain rituals of order when harm happens—even when those rituals do nothing to ameliorate their suffering. For example, many people know no recourse for violence besides calling the police, even if they do not believe doing so will lead to any form of resolution. We have been taught to imagine that “the alternative” to policing is nothing less than brutal chaos. In addition to building relationships that foster collective power, interdependence, and care, then, we must educate people about alternative interventions that actually address the needs of people affected by violence, poverty, and climate collapse. We must also continue to create our own works of visual art, fiction, and poetry that drive people to envision cooperation and mutual aid as our primary responses to crisis.

And we must help people imagine a world in which we can rely on one another. As author and organizer Shane Burley told us: “Solving a problem collectively takes a great deal of faith in others. We have been trained to see our survival in opposition to the community, something we do by putting ourselves and our families first. So it is a big leap to start trusting that collective liberation will actually care for us.”

The mutual aid efforts of groups like the Auntie Sewing Squad and Maeqtekuahkihkiw Metaemohsak can help build that net, Burley says. To have faith that “a liberatory approach” is their best option, some people want to see evidence that we have helped one another survive and that we can do it again. “That’s what building up projects of solidarity and mutual aid does: It creates a belief in what is possible, so that when even larger crises form, we have shown that by fighting the oppression of another we really do have the ability to target our own oppression as well,” Burley told us.

In order to invest in a new vision, and a new way of living, we have to believe in each other and our capacity to create something better. Our belief in human potential must outweigh our fear of human failure. Our imaginations must be courageous.

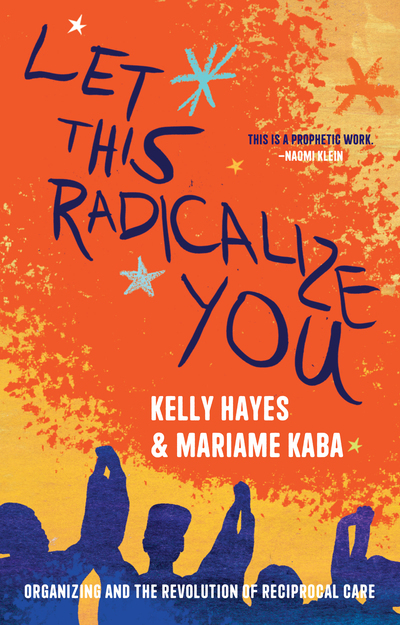

Excerpted from Let This Radicalize You: Organizing and the Revolution of Reciprocal Care. Copyright © 2023 by Kelly Hayes and Mariame Kaba. Reprinted with permission from Haymarket Books.

Image: Christina Deradevisian/Unsplash